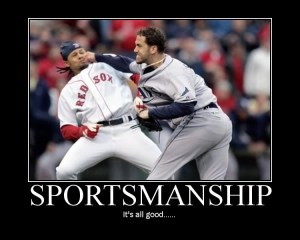

When I come to think about good sportsmanship, I think of simple examples, such as athletes and coaches amicably shaking hands after matches, or opposing players assisting each other when injured. On the other hand, when I consider what bad sportsmanship entails, I think of athletes committing “cheap shots” against their opponents, or coaches heckling at officials. While these acts of sportsmanship share similarities in physically representing different modes of conduct, my interests lie within the internal mechanisms as to why we commit these certain acts. Reoccurring themes from the works of Simon, Dixon, Feezell, and Arnold have interpreted sportsmanship in terms of deep-seated constructs. The focus of their works was not necessarily aimed at the physical interpretations that one makes on the field, but rather, the understanding of the internal contraptions that drive the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ one performs an act of sportsmanship.

After the course of my attempts to understand sportsmanship, I began to ponder about certain issues as a sport coach, and whether or not I have demonstrated good sportsmanship towards game officials and players. More importantly, I have asked myself whether or not I have represented the practice of good sportsmanship for my players. I believe that sportsmanship is a debatable, yet convoluted subject that is based on ideals. It has no specific boundary as to where it really begins or as to where it ends, but we know it is there, and open to one’s individual interpretation. However, a viable fact is that sportsmanship does set a precedent of how individuals within the sporting environment should conduct themselves, as it ultimately contributes to the value of sport.

Collectively, Simon, Dixon, Feezell, and Arnold captured many different and important constructs that define sportsmanship. The ideas that were most interesting were that of Dixon’s rejection to the AB Thesis and his idea on intention behind actions, and how it defines sportsmanship; Feezell’s virtue approach towards understanding ethics and how sportsmanship balances between play and seriousness; Simon’s view on competition’s mutual quest for excellence and contexts of sport; and Arnold’s three approaches to sportsmanship (altruism being the most interesting).

Arnold’s approach to sportsmanship as a form of altruism essentially captures the intrinsic aspect (moral) of games. Arnold claims that altruism, in the forms of action and conduct, believes those who hold true to altruistic values go beyond playing fairly by showing “genuine concern for one’s fellow competitors, whether on the same side or in opposition” (p. 161). As a sport coach, I have witnessed the insensitive actions many athletes partake in during competition. However, I do believe that if altruistic values can be taught by parents and coaches alike, and that they are demonstrated by athletes; I truly believe sports would have a better balance between competitive aggression and warring connotations.

Similarly, another aspect that I have used in trying to understand my coaching philosophy in regards to sportsmanship is Dixon’s rejection to the AB Thesis. The AB Thesis basically states that it is unsportsmanlike for teams to maximize the margin of victory after securing a large enough lead. On the surface, it seems like it would hold water, however, Dixon’s main argument suffices the idea that intentions play a large role in determining what is considered unsportsmanlike. Dixon clearly states that he despises teams that “mock, taunt, and gloat at outmatched opponents” (p. 175). Nevertheless, he believes that teams should show mutual respect, and that if the intentions are not to maliciously humiliate opponents, we should view competitive sport for its primary purpose: the determination of relative athletic ability (p. 172).

As intentions and altruistic values serve as a partial understanding to sportsmanship, the idea of Feezell’s individual virtues of sportsmanship has also assisted in the discernment of my coaching philosophy. Feezell best portrays sportsmanship as a balance between the serious and non-serious aspects of competition, and supposes that “being a good sport is simply an extension of being a good person” (p. 153). Believably, sport should possess a balance between non-serious and seriousness, ultimately creating an environment where coordination and amicability between coaches and players may prevail. However, being a good sport does not necessarily mean you are a good person. Plenty of times have I seen dramatic changes of attitude and demeanor differ between on the court and off the court. Consequently, I find it difficult to link a good sport to being a good person.

As a sport coach, I find myself caught in between the crossfire of competition and sportsmanship. But through careful examination of each of these authors’ work, I have been able to build upon my philosophical foundation and direction as a coach. Furthermore, incorporating altruistic values, intentions, and individual virtues have allowed me to better understand myself as a leader. As mentioned earlier, good sportsmanship sets precedence and contributes to the value of sport. Therefore, it is my ultimate responsibility as a practitioner of sport to instill the moral ideologies of sportsmanship.